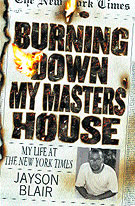

BURNING DOWN MY MASTERS’ HOUSE: My Life at The New York Times

Jayson Blair. New Millennium, $24.95 (248p) ISBN 1-932407-26-X

We know that Blair is a world-class Pinocchio. During his tenure at the New York Times

(1998–2003), he filed perhaps dozens of stories laced with

inaccuracies, lies, deceptions or plagiarisms. The revelation of

Blair’s fraud exploded into the biggest scandal in the history of the

newspaper, toppling the regime of Times executive editor Howell

Raines and managing editor Gerald Boyd. Now, in his first book,

Pinocchio morphs into the Boy Who Cried Wolf—this time, Blair seems to

insist, what he’s telling us is really, really true.

We know that Blair is a world-class Pinocchio. During his tenure at the New York Times

(1998–2003), he filed perhaps dozens of stories laced with

inaccuracies, lies, deceptions or plagiarisms. The revelation of

Blair’s fraud exploded into the biggest scandal in the history of the

newspaper, toppling the regime of Times executive editor Howell

Raines and managing editor Gerald Boyd. Now, in his first book,

Pinocchio morphs into the Boy Who Cried Wolf—this time, Blair seems to

insist, what he’s telling us is really, really true.

How do we approach a memoir by a confessed serial liar? One way is to treat it as fiction, and as such Blair’s tale has superficial merit. The dramatic arc is strong: young black man rises above troubled background to excel at the greatest paper in the world, only to succumb to pressures internal and external. The writing is sharp, too. After all, Blair was a Times reporter, and his prose is as clean and forceful as that of the average Times dispatch. There’s some padding though. In a nod to the book’s subtitle, Blair lavishes attention on his (presumably legitimate) coverage of numerous stories, especially of the D.C.-area sniper case, failing to realize that readers’ interest will fade when he stops discussing the inner workings of the Times and the mechanisms and consequences of his lying.

But we will credit Blair and consider this as nonfiction. The memoir begins with the collapse of his house of cards, then flips back to his early upbringing in Columbia, Md., and swiftly forward to his hiring as a Times intern while at the University of Maryland. Blair’s chronicle of his Times years brims with the inside gossip newshounds love, and he names names while dishing it. Throughout, he levels serious (albeit generally unsubstantiated) charges at the newspaper.

One is racism, in both the Times’s coverage (“The one thing that was clear was that it took a lot of dead Africans for anyone to notice on West Forty-third Street”) and its treatment of employees (“a black recovering drug addict at The Times was not going to be given the same leeway that a white one might be”). Blair claims that Metro desk editor Jonathan Landman, who first cast doubts on his reporting, wrote in an internal note that “minority candidates [for hiring] were always sub-par compared to others.” Then there’s the bartering of news coverage for favors. “Public relations people,” Blair reports, “substituted theater tickets, free meals and drinks and, sometimes, even sex for mentions. Journalists at The Times were considered to have a weak spot for sex....”

Most startling, though, are Blair’s accusations of shoddy journalistic practices condoned by Times management. “The message was clear: getting it right was not as important as getting it fast.” He contends that the Times allowed “star” reporters to slap their byline on stories written in part or wholly by stringers and freelancers, and he exposes what he calls “toe-touch” reporting: “A toe-touch was a popular and sanctioned way at the newspaper to get a dateline on a story by reporting and writing it in one location, then flying in simply so you could put the name of the city where the news was happening at the top of the story. It is hard to imagine how many thousands of dollars are spent on ‘toe-touch datelines’ each month at The Times.” Blair also accuses the newspaper of “no-touch” reporting.

These charges will make the book necessary reading for some, but they serve Blair, too, apparently providing for him some basis for his actions. “The cognitive logic of my belief that I could get away with not visiting a city that I was supposed to be writing from can easily be understood, though not excused”; so rather than reporting from the field, as he told colleagues and friends he was, Blair composed many of his stories while hiding out in his Brooklyn apartment, relying on information from phone interviews and the Internet to fill the column inches. The book, in fact, is filled with excuses-cum-explanations, most of a personal nature. Blair says that for years he suffered from alcohol and cocaine addiction (he’s been sober since early 2002) and from depression, then manic depression, that led him, during his last days at the Times, into psychosis and a suicide attempt described here in detail. And while he claims to take responsibility for his actions, he swipes steadily at the Times and its “callous” managers, and at its “end-justifies-the-means” environment, where he was treated like “a rag doll.”

It is Blair’s notoriety that will first draw attention to this book, and it is his charges against the Times that should push it onto bestseller lists. His rancor, his excuses and his predilection for payback undermine the integrity of his admissions and apologies, however, and will go far to demoting the entire matter and his part in it to a cautionary footnote to the history of journalism. As for the charges, in spite of Blair’s reputation for lying, the Times must respond to them as necessary; thus the newspaper will only increase the transparency committed to by its hiring of an ombudsman, a direct result of the Blair affair. Yet Blair himself remains opaque, despite the book’s confessional nature; the evident slyness of so much of this chronicle speaks at the least of a manipulation of truth. It may be that what we read in this fierce, self-indulgent, self-aggrandizing volume is truth, albeit one man’s version; it may also be that once again the author is hiding out, as it were, weaving fairy tales that we buy at our own risk. Major ad/promo, including 10-city tour and appearances on Dateline, The Today Show, Larry King Live, The View and The O’Reilly Factor. Simultaneous unabridged New Millennium Audio, read by Blair. (Mar. 6)